It is almost the end of Reconciliation Week 2020, and our kitchen table is empty. It struck me hard tonight, as, for reasons beyond my control I faced the prospect of eating alone. Ordinarily I don’t mind a moment of solitude such as this, but tonight I was confronted by it. Our kitchen table has been for me the ultimate place of encounter. It is the place where I can sit down with a literal stranger, offer them a cup tea or plate of food and in the course of one shared meal, come to recognise a friend.

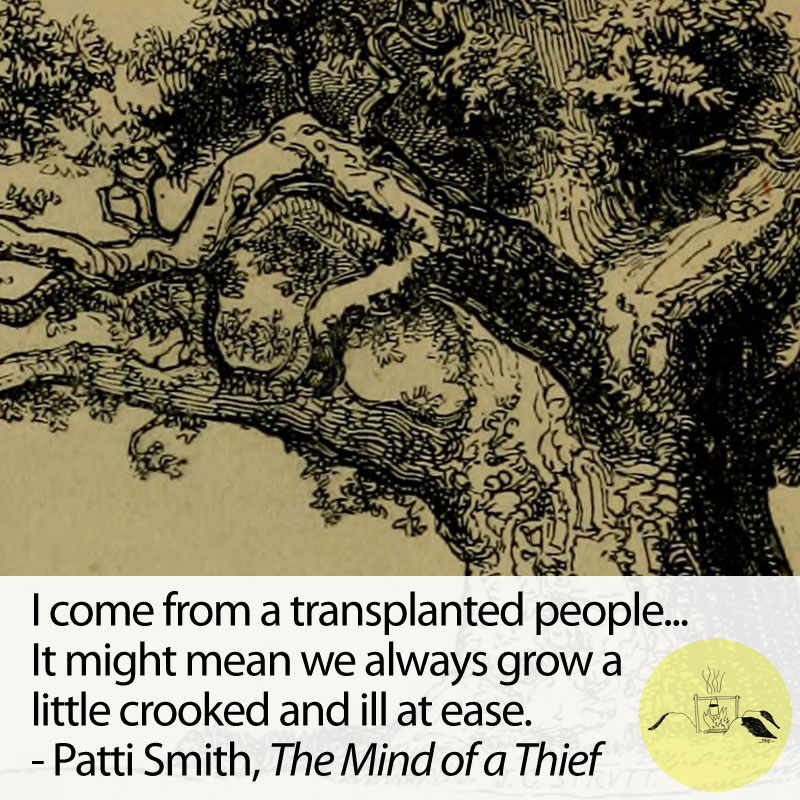

We are missing our Indigenous guests at the moment. The guests around whom we each gather, in order to find our centre-point and focus. The ones who bring us out of ourselves, and remind us who we are. We are a people of radical hospitality, who love and care beyond boundaries of difference. Of course this is never easy, because we host on stolen land. We welcome people in to a place that is not rightfully ours. And yet, in daring to take up that position, our tenuous, fragile, broken attempts at welcome are consistently received with grace. In being honest about the awkward, back-to-front nature of the situation, we find another place to be, which offers us a fuller view of each other, and the truths we share in common.

During this extended time at home I have been listening to a number of different podcasts. I have heard both Stan Grant[1] and Duncan Ivison[2] talk about the potential that liberal democracy has for our country. Briefly put, they believe that if we allow our understanding of democracy to expand, in response to Australia’s unique context then a way may be found for us all within a system created for only some. The idea that we can adjust and shape our systems to meet our actual needs, rather than having to fit them into ready-made boxes greatly appeals to me. It is another way of lengthening the table, rather than limiting entry into the place we all call home.

I’ve been watching a bit of NITV recently, and I’ve really enjoyed their coverage of Reconciliation Week. A common theme that I have picked up, has been the focus on the Uluru Statement From the Heart. This is a document of immense vision and generosity from our First Peoples. I can only imagine the amount of work that went in to such a proposal. However, the good will extended by those who contributed to the Statement, was met with shameful disregard for the spirit and potential that it offered to us all. Every one of us lost something that day. More than land or homes or mining rights, we lost the opportunity to encounter each other in a whole new way. We lost the chance to create another place, a fuller place, based on truth, with room enough for all.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people know the truth of this country, they have lived it, and continue to live it every day. We, non-Indigenous folk need to be made more aware— we need the truth-telling that the Uluru Statement From the Heart calls for, in order to begin the awkward, back-to-front journey from strangers to friends. I believe that if we do this, we—and the systems around us—will have nothing of consequence to lose, and everything rich and meaningful to gain. We will be met with the same graciousness that I have encountered time and again at our kitchen table. We will be met with new friends.

- Mehrin Almassi

Resident Volunteer

[1] Speaking Out With Larissa Behrendt podcast, Australia Day-Identity Division and Hope https://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/speakingout/stan-grant/11077180

[2] The Philosopher’s Zone podcast: Uluru and the Heart of the Liberal State https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/philosopherszone/uluru-and-the-heart-of-liberalism/11889480